More than 300 students from schools in Pomán, Saujil, Capayán, and Huillapima participated in an educational and community process to recognize the natural and cultural values of the Sierras de Ambato. Through the Exploratory Guide and the collective creation of the book “Me contó un pajarito” (A little bird told me), the children shared their views on the water, the hills, the fauna, and the customs that make this territory their home.

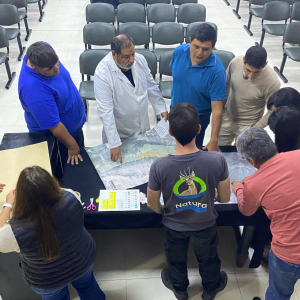

During 2024, we carried out activities training and awareness-raising activities with educational communities, as part of the Sierras de Ambato conservation project, with the valuable participation of educational communities from the municipalities of Pomán, Saujil, Mutquín, Capayán, and Huillapima, in the province of Catamarca.

Using an Exploration Guide, we worked with more than 300 students from eight elementary and secondary schools. This guide was designed as an educational tool that helped us recognize the conservation values of the area through the eyes of children and identify safe and valuable places for the community as a whole.

During meetings at schools, we listened to their voices on issues that affect them: the importance of water, trees, hills, animals, and local customs. We also worked on the threats they recognize in their environment, such as garbage, fires, hunting, and deforestation.

The children clearly identified the conservation values that shape their identity and quality of life:

- Silence,

- Peace of mind,

- The river and the spa as meeting places,

- Medicinal plants,

- Wildlife and

- The water that flows down from the hill and gives life to everything.

The voices and perspectives of children were included in the surveys and management plans for the reserves, so that their feelings would also be part of the decisions about the territory. Incorporating their participation is a way of democratizing the construction of protected areas, understanding that caring for and thinking about these spaces is a task that involves us as a community.

Children from the community played a leading role in the process of creating the Protected Areas. Using exploration guides, they explored the territory with curiosity, observing, drawing, and recording the landscapes, plants, and animals that are part of their daily lives.

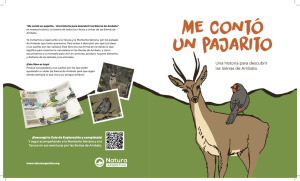

To conclude this process, we present a book of short stories entitled: “A little bird told me. A story to discover the Sierras de Ambato.”

“This book is yours. Because your words and dreams are helping to protect the Ambato Mountains, so that they will always remain what you and your friends dreamed they would be.”

This book brings together stories created by children, narrated by Taruca and Monterita Serrana, two characters who invite readers to dream, explore, and care for these unique landscapes. It is a tribute to what new generations think, feel, and desire for the mountains where they live.

Children bring a unique sensitivity: they observe what adults sometimes fail to see, marvel at everyday things, and find beauty in the small details of the natural environment. Their perspective reminds us that nature is not only to be studied or managed, but also to be felt, listened to, and inhabited with respect and curiosity.

This process left us with lessons learned and a collective commitment to preserve what makes these mountains so special. Most importantly, it left us with the certainty that children’s voices have a lot to say about the future of our territories.

He was an important pillar in the creation, management, and design of the protected areas of the mosaic of municipal nature reserves in the Sierras de Ambato. Each nature reserve is closely linked to the knowledge shared by children, who are the ones who will continue to enjoy their natural and cultural environment in the future.

You can download the book, or listen to the animated version on YouTube.

The Exploration Guide is also available: complete it, and continue accompanying Monterita Serrana and Taruca on their adventures through the Ambato Mountains!

●