Among the Famatina Mountains in La Rioja stands Cerro El Toro, a mountainous formation named for its resemblance to a charging bull. Its dark purple color and imposing presence catch the attention of those who arrive in Villa Castelli, but what makes it unique goes far beyond its landscape: here, the vestiges of an ancient civilization coexist with the biodiversity of an exceptional natural environment, protected under the Cerro El Toro Cultural Nature Reserve.

Today, thanks to a plan to refurbish and revalue traditional trails promoted by the Municipality of General Lamadrid, this site is reopening to the world with renewed vigor. The municipality made the decision and invested in the enhancement, and later Natura Argentina and the Undersecretary of Cultural Heritage and Museums of the Province of La Rioja joined in to work on the recovery of the trails. This collective initiative also included the participation of the local community and specialists in archaeology and conservation.

Due to its invaluable cultural legacy, it was declared a Provincial Historic Monument in 1985 under Law No. 4565. Likewise, due to its outstanding biodiversity, it also obtained the distinction of Provincial Natural Monument. In 2008, the municipal ordinance passed declares this entire area as the Cerro El Toro Cultural Nature Reserve. In addition, the Reserve is governed by National Law No. 25,743 on the Protection of Archaeological and Paleontological Heritage, and Provincial Law No. 6,589 on the Regulation and Control of Archaeological, Urban Archaeological, Paleontological, Anthropological, and Historical Cultural Heritage in the Province of La Rioja. Its dark purple color and imposing presence catch the attention of those who arrive in Villa Castelli, but what makes it unique goes far beyond its landscape: here, the vestiges of an ancient civilization coexist with the biodiversity of an exceptional natural environment, protected under the Cerro El Toro Cultural Nature Reserve. /Enzo Ellero

Renovate to preserve and discover

The project began with a need: heavy rains were causing soil loss on every slope, putting traffic and the conservation of the site at risk. The work was meticulous: stones were rearranged, edges were reinforced, and techniques that respect the landscape as much as possible were applied.

It is located 6 km from the town of Villa Castelli, at kilometer 154 of National Route No. 76, on the eastern slopes of the Sierras de Famatina. It is 34 km from Villa Unión and 35 km from Vinchina. The route is in excellent condition and, upon entering the Reserve, the road is gravel and accessible by vehicle. /Enzo Ellero

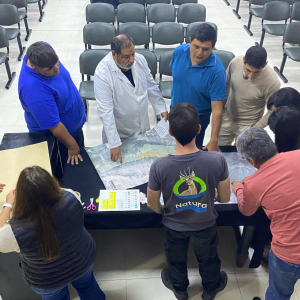

Andrés Baissero is a technician at Natura Argentina and explains part of this process while pointing out elements of the landscape: time was spent analyzing what had been done in this place, how people in the area use it, and what could be improved from a sustainable tourism perspective. “Everything was done in multidisciplinary teams. Previous archaeological studies were respected, but a new and collaborative narrative was developed, which was constructed together with Proyecto Ambiental, specialists in the field. All the local guides also participated,” he summarizes.

Rocío Cardona is also a technician on this Natura Argentina project. The technical team not only contributed their knowledge, but also actively participated in the work journeys, which were joined by municipal and provincial workers and student volunteers. They enthusiastically tell us that they even worked in the rain and snow. The result is low-impact trails that respect the original layout from an archaeological perspective, but with corrections to prevent erosion from rain, among other details.

“We moved material from other areas and then built the trails. Now the intervention seems minimal, almost imperceptible,” explains Rocío, pointing to the little path that climbs the mountain.

The process was supported by previous archaeological studies, which served as the basis for defining each intervention. In addition, two interpretive trails were designed, with the script developed in collaboration with the Environmental School and local guides. /Natura Argentina

This does not mean that the trails do not require maintenance, nor that they do not involve the deployment of local resources to ensure an interesting experience for visitors. In fact, the process also included training technicians in trail refurbishment, leaving the community with the capacity to sustain this work over time. Damián, the guide accompanying us today, shows us the route and concludes: “Working together in this place has been wonderful. This site is unique in the country and can be visited in our department.” The refurbishment not only improved the trail’s accessibility, but also restored its ancestral character: a path that links the past and the present.

Damián, local guide: “Visitors will find here the history of the Aguada culture, remnants of their homes, their enclosures, the rock art they left us to understand their worldview and the importance of this place.” /Natura Argentina

A landscape that preserves culture and wildlife

Cerro El Toro is much more than just a natural setting. Between 770 and 1400 AD, populations linked to Argentino lived here, identified by the “Aguada” ceramic style, which occupied different territories in northwestern Argentina. Their mark is still recognizable in the stone dwellings, the architecture that blends in with the hill, and the petroglyphs of jaguars and human figures.

Aguada rock art consisted of figures and drawings carved into stone using the technique of chipping and scraping. Among the petroglyphs with anthropomorphic motifs (representations of humans and animals), three figures can be seen wearing an unku (a fine woven Andean tunic) with jaguar spots. These rock art manifestations were part of the ritual and religious belief system of the groups or individuals who lived there, shared by most societies in the Valliserrana region.

The Reserve also boasts extraordinary natural wealth: from the Andean Condor to the Famatina Tail-less Lizard, a microendemic species exclusive to the region.

Walking along these trails is like immersing yourself in the daily life of those who inhabited these mountains: seeing the homes that sheltered families, discovering the ancestral engravings that were part of rituals, and appreciating the mountain range from a unique perspective. Damián left us here for a moment, asking us to pause, and in that shared silence, we were able to understand the beauty of the place. You have to come here, treat yourself to a break in front of the mountain range, and experience it.

●

How to visit

Cerro El Toro is a Provincial Historical and Natural Monument, and can be visited with a certified local guide. Guided tours can be requested at the General Lamadrid Municipal Tourism Office.

Here, among hills that resemble mythological animals, petroglyphs that tell stories, and landscapes that transform with every ray of sunlight, visitors discover that the true magic of this place lies not only in what can be seen, but also in what has been preserved thanks to collective effort.

This Natural and Cultural Reserve has a visitor center equipped with services such as accessible bathrooms, internet, hot water, tourist information, and a cultural market that today gives visibility to local crafts with product sales and a recreation area.

What can you do?

- Trekking and hiking

- Archaeological site

- Flora observation

- Wildlife observation

- Panoramic views

Open every day from 9:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. Rates: Admission prices can be consulted by calling: 3804 865393 / 3825 573602 / 3804 864800. According to municipal ordinance No. 178/21, visitors must be accompanied by a tour guide to enter this archaeological heritage site. To reserve a guided tour, please call the tourist information office.